The UK government’s Commission on Racism and Ethnic Disparities has released a controversial new report which argues that there is no institutional racism in the UK and that the UK is an example to the world on issues of race and racism. The Career Guidance for Social Justice website would welcome further commentary on this report and its implications.

In this post Emily Róisín Reid and Dr Sadie Chana of the University of Warwick explore the controversy around the report, assert the value of critical race theory and argue that there is clear evidence of institutional racism in higher education and the graduate labour market.

Powerful and knowledgeable voices have already skillfully articulated from the position of their expertise and significant experience why this report is so harmful: to name a few Professor Kalwant Bhopal in the Guardian, Professor Kehinde Andrews on Talk Radio, John Amaechi’s reflection and David Lammy’s tweet (which says it all).

In 2018, we established the Attainment/Awarding Gap Working Group at Warwick Medical School. We have been engaged in wide-ranging and critical work at our School with the ultimate purpose to eradicate this gap. In so doing, we are working to remove systemic barriers in every element of our curricula: everything from our admissions to our assessment practices inclusive of what we teach and pedagogical practices. We wanted to speak out against this report, by reflecting on Critical Race Theory, talking a little about institutional racism, and thinking how this impacts on education, careers and labour market destinations in minoritized groups.

Critical Race Theory

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a legal and academic movement which looks at the relationship between race, racism and power. It assumes that racism is normal in society, rather than something which is aberrant. By extension, institutions and social structures can therefore be understood to be inherently racist. As the concept of race is socially constructed, CRT explains that racial inequality emerges from social, economic and legal differences that are created to maintain social hierarchies. They are perpetuated through day-to-day dispositions, values and cultural practices which are enacted to benefit those at the top of the social hierarchy who ultimately have an interest in maintaining the status quo. CRT also holds that dismantling racist structures is possible if a critical mass are able to alter the status quo. However, as Delgado and Stefancic put it, because “racism advances the interests of both white elites (materially) and working-class people (psychically), large segments of society have little incentive to eradicate it”.

The relative position of individuals in each group can be comparatively higher or lower compared to their counterparts (in terms of pay, labour market prospects etc.). The main distinction between a disadvantaged white individual and a disadvantaged person of colour is that the former’s position is not determined or maintained due to their skin colour.

Institutional racism in practice: Awarding gaps

We’ve chosen one example to highlight how CRT can be helpful in understanding how institutional racism manifests. Degree awarding gaps (formerly known as ‘attainment’ gaps) are the difference between student from different ethnic and racial backgrounds, including Black, Asian and students from other ethnic minority backgrounds as well as their White counterparts in being awarded a first-class or upper second-class honours degree classification.

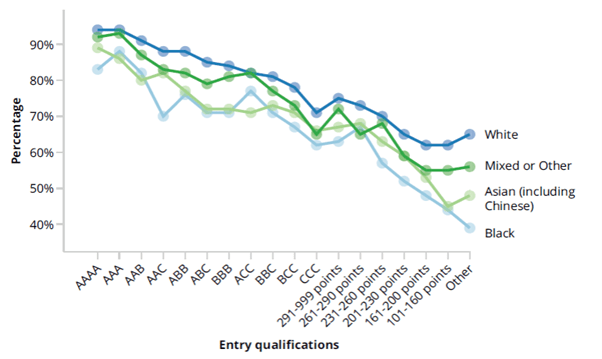

This graph is taken from a HEFCE report on differences in degree outcomes. It uses data across Higher Education (HE) in England, and shows how (Home/UK) students from Black, Asian and Mixed ethnic backgrounds who came into HE with AAAA (far left on the x-axis) performed less favourably in their degree than their white counterparts who came in with the same grades (Total % – y-axis).

It shows that students from Black, Asian and Mixed ethnic backgrounds are less likely to achieve a first or upper second class degree compared to their peers who are White. Controlling for entry qualifications (x axis), Black students are between five and 26 percentage points less likely than White students to get a higher classification degree, and Asian students are between five and 17 percentage points less likely. The differences exist at all levels of entry qualifications, so are equally apparent among students who enter higher education with very high prior attainment in addition to lower attainment. Stevenson and other researchers have investigated the causes of differential attainment, and has found these to be multifactorial but include pedagogical and assessment practices, lack of representation in tutors and role models, lack of access to support networks, feelings of isolation and lack of sense of belonging, imposter syndrome, lack of staff awareness of issues.

The persistence of differential attainment provides one example of many that highlight that our institutions and establishments practices are currently stacked against individuals from minority groups. The blunt gaslighting of the race and ethnic disparities report yesterday smacks hard in the face of data such as these.

“There is also an increasingly strident form of anti-racism thinking that seeks to explain all minority disadvantage through the prism of White discrimination. This diverts attention from the other reasons for minority success and failure, including those embedded in the cultures and attitudes of those minority communities themselves” (p.27)

“This requires us to take a broader, dispassionate look at what has been holding some people back. We therefore cannot accept the accusatory tone of much of the current rhetoric on race, and the pessimism about what has been and what more can be achieved.” (p.27)

Using overtly racist language (italicised), the report blames minoritised groups for their ‘success and failure’ – and denies the significant role institutional racism plays in this. Linking back to CRT, the purpose this serves is to continue to uphold the status quo.

Access to HE for the working class and attainment in education

Whilst there is an intersectional experience of class and race, the report engages with this in a very superficial way and does not provide the necessary detail to outline the varying ways class and race intersect for those who are Black, South Asian, East Asian, Mixed, Other or White ethnic and racial groups. This nuance would be invaluable for understanding how issues relating to working class students can be addressed in terms of access and attainment, and whether and how those approaches may need to be adapted to suit the needs of different ethnic groups.

“Another revelation from our dive into the data was just how stuck some groups from the White majority are. As a result, we came to the view that recommendations should, wherever possible, be designed to remove obstacles for everyone, rather than specific groups.”

Although the data suggests that students from Black, Asian and Mixed backgrounds are more likely to get into HE than their White counterparts, it downplays the significance of awarding gaps in enabling these students to perform to their potential. It minimises the fact that the fewer white students that do attend Higher Education, do significantly better without offering any explanation. The report makes a huge omission by failing to acknowledge the systemic challenges that working class students have had to overcome to get into HE, nor the ongoing systemic issues the minority students will encounter throughout the course of their educative and working lives. These omissions are at huge cost and deny issues such as the awarding gaps which evidence the institutional racism at play.

Careers and the labour market

The report fails to acknowledge institutional racism as causative of attainment gaps, and similarly fails to that declare institutional racism has a stake in the labour market. Fickle explanations are unable to defend report findings that show that although fewer white students attend Higher Education, those fewer students do better, and earn more than students from ethnic minorities. The manner in which the report is written insinuates minority groups are to blame for accessing lower tariff universities or for obtaining lower grades than white counterparts:

“One explanation is that students entering low tariff universities are less able to compete against those from higher tariff universities and are therefore less likely to secure employment in their chosen career. As ethnic minorities are disproportionately more likely to attend these universities, this may limit their employment choices and earnings in later life. Another explanation is that ethnic minority students, and especially Black students, from lower social status backgrounds are not being well advised on which courses to take at university.”

From a careers guidance perspective, as always careers guidance is seen as the panacea to the problems that plague HE. Even fervent believers in the powers of career guidance are aware that guidance alone can’t surmount systemic racism.

As with most UK policy reports of late, calls for and praise for good career guidance is loud and clear. However, what doesn’t appear in this report so much is calls upon the government to fund it, or any indication of a need to prioritise groups. A correlation is noted between engagement HE careers advisory services and higher-skilled graduate occupations, albeit seemingly indicating that those with more social & cultural capital are the ones who know to to seek out this support. The case for careers advice being particularly important for students from first-generation to HE backgrounds is however clearly made.

The language of the report is very much in keeping with the neo-liberalist rhetoric we have come to expect from this government. There is an undercurrent which fails to recognise the inherent value of arts and social science subjects, seemingly diminishing them as “subjects with multiple or less obvious career trajectories” (p.96). Reading a report around race and ethnic disparities, one might be forgiven for expecting some bigger picture thinking about attracting and supporting minority representation and leadership in all professions (including Business, Creative Arts and Sociology) and supporting this might be a benefit to society, but sadly this was missing.

Careers for social justice and closing thoughts

Careers practitioners operate as part of a system (schools, FE/HE, adult careers sector etc) and by function of their work, can sometimes be the source of opportunity. There are individual pieces of action that careers practitioners can take to support minority ethnic groups, in terms of advocacy and support as well as conventional information, advice and guidance. Collective action is needed in order to recognise and tackle systemic issues. We need to encourage more representation from minoritised backgrounds into the careers profession and amplify their voices to be able to change the systems.

A starting point for each person to enact, now, is to critically engage with this and question why this report has been commissioned, by whom, for what purpose:

“We understand the idealism of those well-intentioned young people who have held on to, and amplified, this inter-generational mistrust. However, we also have to ask whether a narrative that claims nothing has changed for the better, and that the dominant feature of our society is institutional racism and White privilege, will achieve anything beyond alienating the decent centre ground – a centre ground which is occupied by people of all races and ethnicities.”

As a collective of career guidance practitioners, we need to push for more funding for career guidance, to be undertaken by qualified careers professionals. We need to begin to question, individually and collectively, what power we have and the ways in which our roles can serve to enable the status quo of current systems. We might be unaware of the power we hold, and the time to become aware of this power, is now. Acknowledging that institutional racism exists, and identifying ways in which this can be addressed are the first steps that must be taken in order to dismantle it. We needs to stand together, embrace the discomfort and only then will we be able to move forwards.

It is so important that you have written this post. The government’s new report is essentially asking us not to trust what we can see in front of our eyes. There is a desperate need to provide evidence that demonstrates the range of structural and institutional ways in which racism operates.

LikeLike

[…] Many black and ethnic minority business leaders have expressed disappointment at the report, viewing it as a missed opportunity. Elsewhere Emily Róisín Reid and Sadie Chana of the University of Warwick have argued that the report misses clear evidence of institutional racism in higher education and graduate careers. […]

LikeLike

Thank you Emily and Sada. Really useful. I have not read the report properly yet. I was shocked to see some excerpts such as the sentence which diminished the history of slavery. You’ve got me thinking about how to introduce this topic in my teaching about career development and employability with students too.

LikeLike

[…] Many black and ethnic minority business leaders have expressed disappointment at the report, viewing it as a missed opportunity. Elsewhere Emily Róisín Reid and Sadie Chana of the University of Warwick have argued that the report misses clear evidence of institutional racism in higher education and graduate careers. […]

LikeLike