I was introduced to the idea of troublemaking around 10 years ago during a feminist pedagogy course, and it really caught my fancy. In my enthusiasm, I ended up creating too much trouble at my first workplace fresh out of graduate school, and had to rethink how I could trouble the curriculum strategically, especially while working within an educational institution. I think of a strategic troublemaker as a Trojan horse, who is apparently teaching the standardised curriculum, yet who might occasionally slip in conflicting content that questions its taken-for-granted facticity.

Troubling the curriculum is an important anti-oppressive pedagogical approach as it aims to disrupt the hegemony of the standardised curriculum which often represents the values of the dominant culture. Anti-oppressive education is often focused on educating the ‘other’, and is about expanding access, and it also may be about empowering the ‘other’ through the development of a critical consciousness regarding the sociopolitical processes shaping their disempowerment. But, how can we be anti-oppressive educators while working with young people from privileged backgrounds who can potentially reproduce oppressive structures through the careers they choose? Troublemaking can be a particularly crucial pedagogical strategy in careers education to deglamorize and recode what particular careers mean for young people from privileged backgrounds, and for them to reflect on how they might reuse and redistribute the resources they have in anti-oppressive ways.

When I started curating content for a careers education firm serving middle-class to elite English-speaking schools in India, One Step Up Educational Services Private Limited (henceforth, OSU), I had to make my troublemaking philosophy more explicit with the marketing team (who would sell these modules to schools), and to the student engagement team (who would be the troublemakers in the classroom). These interactions generated much dialogue between what was primarily a functionalist and instrumentalist approach to careers education with clients, (schools, parents as well as children), and a social justice (conflict or critical theory) approach. Indeed, the question often was how do we make troublemaking palatable or saleable, quite a paradox!

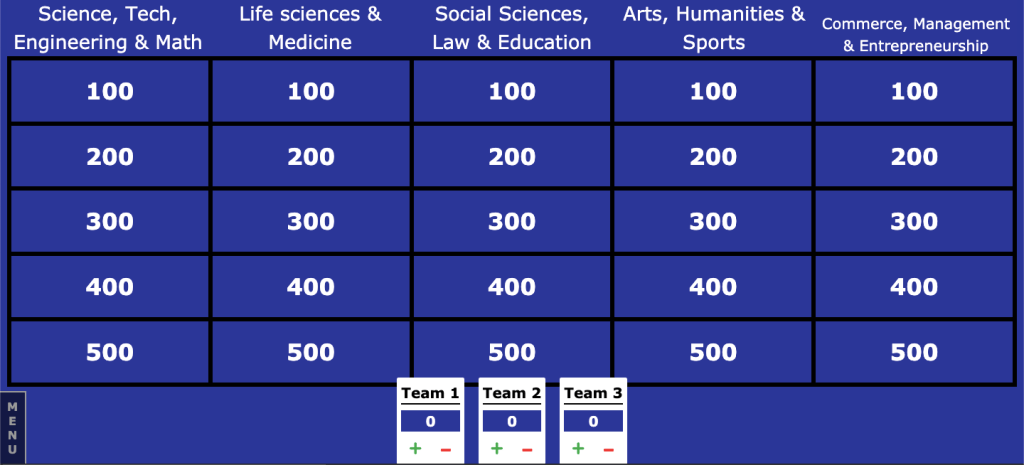

In this post, I describe the Careers Jeopardy module to illustrate how we conceptualised and enacted troublemaking in careers education. We used a modified version of the Jeopardy quiz game to make the class interactive and fun. We briefly introduced Johan Galtung’s concept of the violence triangle, and related concepts of direct, structural, and cultural violence from peace studies. We informed the students that the quiz was dependent on them learning these concepts so that they would engage more deeply with the concepts. The topics in the Jeopardy games were based on subject streams: STEM fields, Biomedical sciences, Social sciences including education and law, Humanities, and the Commerce and Management fields (see image below). Within each topic, there were five levels of situations with increasing difficulty and dollar amounts.

Each situation described some kind of violence (physical, psychological and symbolic violence based on gender, caste, religion, disability, class difference) in that particular area of work taking examples of real-life events in the Indian or regional context. Students had to name the violence that was happening in that particular situation within the field (in the form of a question as the Jeopardy game goes), and articulate their understanding of it (see image below for an example).

The activity had several purposes such as to firstly disrupt the nobility or grandiosity associated with particular careers such as engineering and medicine, secondly, to explore the practical and political problems that fields grapple with, and to think about career choice in terms of choosing problems that motivate them to work towards, and finally to recognise invisible forms of violence in different contexts of work.

I invite my colleagues from OSU to share their experiences and challenges of “selling” and “doing” this particular module in the comments section and/or as separate posts. For instance, the word, “violence” often triggered discomfort among principals. We stressed on the word “peace” and the more innocuous sounding social-emotional learning life skill of “social awareness” to package this module. I’d also love to hear readers’ thoughts about this activity, in particular, the pedagogical, practical, and/or political issues you anticipate as well as how you engage in troublemaking in your own work.

I can’t say how much I love the idea of our work being a kind of thoughtful, well organised and structured trouble making. I work mostly with PhDs and researchers and I am often sad and frustrated at how browbeaten they can be by their institutions and senior colleagues. The whole point of research is to disrupt existing knowledge and perspectives and this approach is far too often only honoured in the breach. Thanks so much for this – I am going to think about how I can apply it in my work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing the context of your work. Especially now but also before Covid, it IS a struggle for students/early career researchers to push back and ask for empathy for the fear of being seen as too aggressive or demanding or selfish. I like how you say that trouble making has got to be a “thoughtful, organised and structured” strategy :), and it makes sense if students want to push back, a career guidance professional can support them in developing such a strategy.

LikeLike

Thank you for such an interesting post. How did the tutors react to the implicit idea that they were part of the structural/cultural violence? I am interested in ideas behind ethical career choices and Galtung seems such a perfect fit for this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good question! In India, one of the challenges for students is that they often do not make choices for themselves based on their interests but are often directed to careers based on parents’ preferences which are often status-based (at least for this demographic), which is also gender or caste based. Hence, the politics of most facilitators was to enable students to make choices based on their own interests and preferences, that is, to deal with the structural violence that children do not get to make their own choices. But, not everyone thought that looking at careers from a peace studies lens was a relevant approach for career guidance even if they appreciated the point of it generally. So, they kept getting us back to “practical” issues. For instance, arguments were made that parents (who pay for these modules) may not be interested in such a module or may even get agitated by such a module, or how is this useful for children in making a career choice. So, they really pushed us to think as a group on the utility of this approach. And one way in which we articulated how this approach might be practically useful is that students get to explore their interests from this lens, and tell their career stories in a meaningful way using this lens which would be useful during college application essays or interviews.

LikeLike

Thank you for the detailed reply. I could see how it would help students articulate how gaining the role they want would help them make a positive impact on the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the use of Jeopardy here. It is a perfect hook to get people thinking. I’ve not encountered the violence triangle before – but I think that it is very useful. It has some similarities with Young’s faces of oppression https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iris_Marion_Young which Ronald Sultana introduced me to and I’ve used quite a lot in relation to career guidance and social justice.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Tristram! Yes, the jeopardy game was definitely a good hook but sometimes it was restrictive because most of the situations could be read as having direct, structural, and cultural violence happening simultaneously and interacting with each other. So, we debated on whether we should give points only for the official correct answer or if they could be given points so long as they could justify their answers.

I have read yours and Ronald’s article where you discuss Young’s five faces of oppression- I agree, there are some similarities between the two! Thank you for bringing it up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Aditiarur,

What a great article! I think the concept and theory of ‘troublemaking’ is a brilliant one. It sounds rebellious and anti-establishment but that’s just what is needed to help to develop and raise the consciousness of clients we work with especially privileged ones. The fact is the curriculum and the orthodox careers approach would benefit from a subversive pedagogy like this. Thanks for sharing the Careers Jeopardy board game to challenge different types of oppression and link it to careers education. It would be great to see how it works in reality! I would attend a webinar or online workshop if you did one!

Hope, you have a very nice week ahead!

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] Troublemaking in careers education. Aditi Arur explains why we need to be willing to make some trouble in careers work and disrupt the hegemony. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person