In this article Jouke Post responds to Russel Muirhead’s book Just work and discusses the division of labour in society. Jouke is a researcher at the Saxion University of Applied sciences and a career expert at James, a career division of the Dutch trade union CNV.

Why is it good, right or just that a certain person does certain work? How do we justify the large qualitative differences in the division of jobs between people? Why do most of us have good and nice jobs and while others, like migrant workers, have bad, unpleasant and unhealthy jobs?

In Just Work the political philosopher Russel Muirhead addresses a lot of career related issues. They circle around the moral foundations of the division of labour in a society. The concept of fit guides his quest for answers. His thinking complements traditional and well-known matching theories on career development, such as those of Parsons and Holland. In my view, the added value of this book consists in linking fit and matching concepts to democratic values, like justice and freedom. I will summarise his arguments in this blog and conclude with important lessons regarding the plea for social justice.

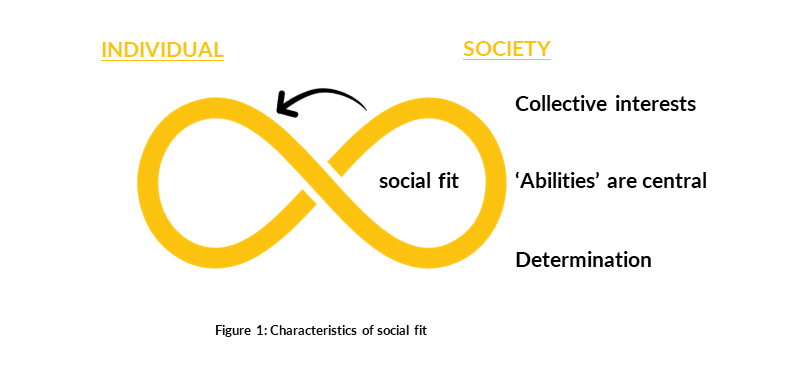

In answering the above questions, Muirhead distinguishes two kinds of fit: social fit and personal fit. The first kind of fit can be aptly illustrated by Plato’s The Republic, written in 380 B.C. In this dialogue Socrates raises the question how a ‘simple city’ can be adequately organised, including the division of labour: who does what and, above all, why?

That people should specialize in certain work is obvious to Socrates, only then will they produce both more and better work. But what determines the nature of that specialisation, what makes someone the ‘right person in the right place’? The basis for a right or just division of labour, according to Socrates, is the natural disposition of people: “one has a disposition for this and another for another function“. Roles and tasks are assigned to people that fit their individual nature and aptitude. The next question is of course how these differences in disposition between individuals can be explained and justified. Socrates leaves this question unanswered and Plato ultimately needs a myth to justify this difference between people. In this myth, people are given different metals mixed into their souls at birth, which constitute the different classes of the city. These metals determine the occupations for which each person is suited.

This ancient approach to aptitude is an illustration of ‘social fit’ (Figure 1): the question of who could, and ultimately, who should do what work, is determined primarily by where someone adds the most value or utility in the collective interests. Here, the person’s innate ‘ability’ is decisive for his or her suitability. It takes a myth, and later in history a religious or political morality, to justify this division, in which some deserve better jobs and careers than others. Individual freedom and choice have little to no place in this ranking: the individual conforms his suitability to the greater good. For most of history, careers have predominantly been determined by this kind of individual inherent characteristics, in which the position of an individual in a society is determined by a given classification.

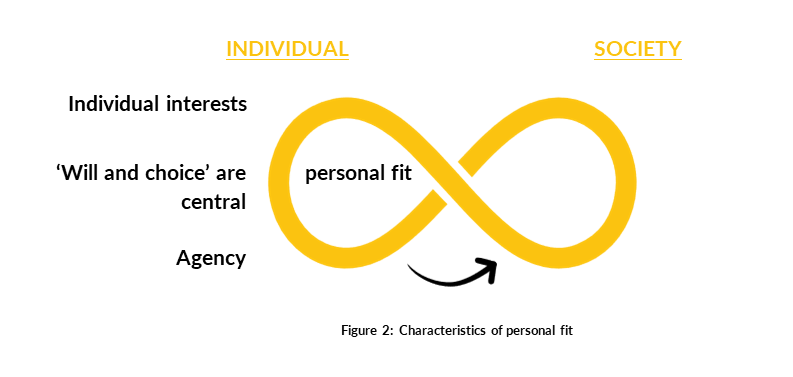

Since the 19th century, due to industrialisation, a very steady change in this social hierarchy took place in Western Europe, among others. Not so much origin and background, but talent and performance started to determine social position. Space for personal development comes about and this offers opportunities for social mobility. Education acquires a powerful lever in this new, meritocratic and dynamic system. Muirhead summarizes this shift in thinking about fit and matching under the heading of ‘personal fit'(Figure 2): the qualities and desires of the individual constitute the primary orientation in one’s career development, and study and work roles are always sought to match these. Decisive and guiding in this type of fit are ‘freedom’ and ‘will’.

In Muirhead’s classification, matching can thus be approached from a social, public and collective perspective (social fit), and also from an individual perspective and interest: the person’s preferences and characteristics (personal fit). Social fit and personal fit are both opposite and complementary; they can also be used simultaneously. It is evident that in the field of career counselling and job coaching, the doctrine of personal fit is leading: counselling is rooted in the belief and ideal that people want and are able to do work that best fits their characteristics.

The difficulty of combining social fit with personal fit reflects a provocative question at the heart of justice: can we all get what we ‘deserve’, and meanwhile also make our contribution to the common good? When some do work that suits them poorly (personal fit), such as migrant and precarious workers, but which contributes to important collective goals (social fit), this question comes into even sharper focus: why are some restricted in their enjoyment of work and freedom of choice, so that others are allowed and able to thrive and grow in their work? Why do people who do the necessary and useful work that almost no one else wants to do get no recognition and low pay? Muirhead’s book exposes these ‘inconvenient truths’ of our labour markets and career development very sharply and profound.

Ultimately, Muirhead concludes that social fit and personal fit are difficult to reconcile and must be conceived as incommensurable. Social fit puts too much emphasis and priority on what is necessary and useful for the common good and neglects the preferences of the individual. Justice, conceived as giving each person what he or she deserves, requires that the interests of individuals count, and social fit is therefore inadequate for this purpose. Personal fit is a worthwhile pursuit, but for many workers it will not be able to fulfill its promises of freedom and self-actualization. For even in advanced economies, there still exists work that is inconsistent with the preferences and dignity of the people doing that work. Precarious labour, as illustrated so adequately and wry in in the film Sorry, we missed you, is tolerated in modern society and not easy to combat.

The ideal of fit constitutes a so called regulatory ideal for politicians, policymakers and professionals: an ideal that is not easy to achieve but worth striving for. It reflects the inherent tension in the nature of work, i.e. the tension between necessity and freedom, between work as a burden and work as a blessing. These dueling possibilities of work have always existed and must be seen as the essence of work. Work will never be a perfect fit for our freedom and our will and will always contain elements of discipline, adaptation and sometimes coercion. But the regulatory ideal of fit does underscore our dignity as (working) human beings and provides a moral dictionary to indicate why certain labour is an assault on that same dignity, e.g. in sweatshop labour. Moreover, between poor and minimal social fit and good and optimal personal fit, there is immense room for improvement. Both the job design and working conditions of precarious, monotonous and repetitive work, for instance, obviously require adjustments for the better. Inhumane work is a choice and some people appear to be more unequal than others (see Frank Pot on monotonous and repetitive work).

Muirhead’s analysis thus also provides a strong rationale for the struggle for decent and sustainable work. Reading and immersing myself in this book has learned me two important lessons. First of all, I realize more deeply that the world of work as we happen to find it in our days, is contingent: it could have been (very) different. And as a consequence of this awareness: it doesn’t have to be and stay like this. Thinking in terms of social and personal fit offers us an adequate framework to repair, rebuild and design the world of work, jobs and careers, so that it better resembles the ideal of social justice.