Tristram Hooley discusses the current economic crisis in the UK and what it means for the careers profession.

The UK is currently in the middle of a labour market crisis. A variety of factors including, Brexit, people exiting the labour market during the pandemic, inflation, many businesses carrying debts from the pandemic and the whole economy teetering on the brink of recession, are seeing businesses struggling to fill vacancies and the economy struggling to grow.

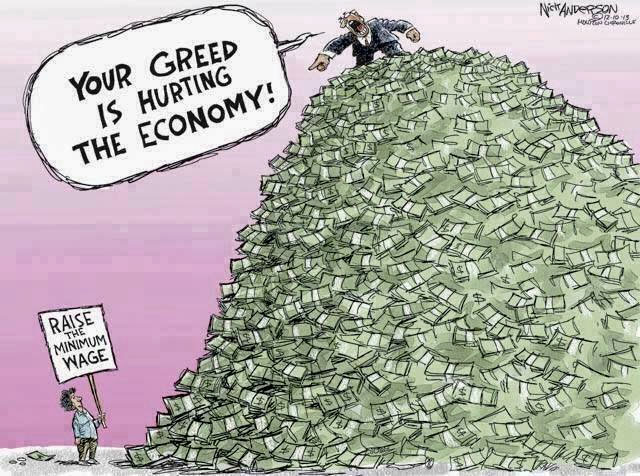

The private sector is pushing up wages to deal with these issues (albeit not as fast as inflation is rising). The government is seeking to hold down public sector pay, in part out of fear of the dreaded wage-price-spiral. But as Grace Blakely explains in Tribune, as inflation isn’t being driven by wages, it is unlikely that increases in wages will lead to a wage-price-spiral. Indeed, if workers don’t fight for higher wages we are likely to see a major drop in living standards.

Fightback in the public sector

Thankfully all across the public sectors workers are fighting for their pay to keep up with inflation. Plans for a co-ordinated national day of action will see what are currently a series of local disputes, come together into a national movement. The cost of living is going up, private sector wages are going up, and so public sector wages will have to do the same, otherwise the public sector will empty, with those remaining impoverished.

Ultimately the campaigning and collective bargaining will result in an offer for public sector workers. My guess is that the government will offer nurses and health workers 7-8% and then everyone else will fall in behind that figure. Effectively it will be a national settlement, although because the UK likes to do everything the difficult way it will be bitterly implemented through a thousand different sectors, agencies, quangos and government sub-contractors.

Why is this a problem for the career guidance profession?

Career guidance is fragmented across a range of different sectors. Those career guidance professionals employed in higher education, or in relatively secure and recognised roles in the schools sector, will ultimately benefit from the wider settlement negotiated by the education unions. This is why I always argue that it is important for career guidance professionals to be part of trade unions. Ultimately this is what guarantees you decent work.

But, a very large segment of the career guidance profession are outside of these kinds of collective bargaining structures, and yet not in the private sector in any meaningful sense. Career guidance in England was privatised in the early 1990s and since then there has been a gradual erosion of the mostly not-for-profit companies that emerged in the aftermath of the privatisation. Career guidance companies are now typically small, beleaguered and reliant on poorly paid government contracts. This pattern can be seen in the National Careers Service, in the limited services outsourced by local government, in some contracts offered by the Department for Work and Pensions and in the outsourced work available from schools and other educational institutions.

The situation for career guidance companies is made worse by the fact that they are struggling to get suitable and sufficiently qualified careers professionals to work for them. They are operating on such tight margins that there is very little opportunity for such companies to increase salaries and this is made worse when they are understaffed and unable to meet the targets set in government contracts. Careers professionals are faced with the choice of leaving or staying and getting progressively poorer.

This is the reality of a privatised and underfunded careers service. Not freedom from government interference or an explosion of entrepreneurialism (indeed, where would such entrepreneurial income come from?), but rather an impoverished and poorly staffed sector struggling to deliver against impossible targets dreamt up by civil servants with little understanding of the nature of the quasi-market they are designing or the purpose that it is trying to achieve.

So what is the solution?

In a sense the solution is easy. Career guidance needs more funding. The National Careers Service, more funding, the public employment service, more funding, local authorities, more funding, schools, more funding, further education, more funding. You can spot the pattern. There is no other obvious answer to these problems. You can trim back and live on reserves and goodwill for a while, but ultimately there are limits.

So, government needs to fund career guidance better, and once that money starts to come, career guidance employers need to rapidly start raising wages. I understand that this is a risky strategy, but after more than ten years of wage stagnation and decline, there is a desperate need to move in the opposite direction. Depressing pay ultimately hurts the viability of the whole sector.

The Career Development Institute needs to start talking about money and pay much more. It isn’t a trade union, but it can’t ignore the fact that the future of the profession is bound up with people wanting to do this job, and that is bound up with money. And, careers professionals need to join a union and stand up for their own rights. As a profession devoted to making other people’s working lives better, we have allowed our own living standards to decline over the last decade. This needs to stop!

Careers professionals need and deserve decent work and decent pay. We need to say this, say it loud and keep on saying it as we move forwards into what will hopefully be a better future. We only need to look at the personal wealth of our prime minister to remember that the problem is not a lack of money, it is the distribution of it.

I love this piece, thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts about the worrying trends and the needs to be able to continue in this profession. I agree wholeheartedly!

LikeLike

[…] most popular post of the year was written back in January, by me! In it I looked at the economic crisis that the UK was (is) going through and reflected on why it was particularly problematic for the […]

LikeLike