My default instincts as a practitioner were to avoid asking questions about individual family backgrounds in standard advisory interactions; this was borne out a desire to avoid assumptions about what, if any, family individuals might have. Therefore, when I conducted research as part of my PhD into graduate transitions I wanted to use the opportunity to discover more about the role of family, something that I had only ever skirted around as a careers adviser. My questions in research interviews addressed how graduates viewed the role of family in influencing and supporting them as they started out in their careers. I wanted to find out more about how graduates made sense of their social connections as I had become increasingly aware of inequity in the graduate labour market and how socio-economic backgrounds contributed to this. As I had read and observed so much about differential social capital based on social class, I was particularly interested to uncover the details of ordinary working class lives.

In my research, I was really struck by the important role of families in providing support. This could be in a variety of ways – not least as economic and emotional safety nets. Social support from family emerged across all interview participants (n20) in my study although manifest in different ways. In particular, my findings led me to question default depictions of working class graduates, which tend to emphasise what they lack compared to their more advantaged peers. I do not argue for an idealised presentation of working class families or seek to gloss over structural inequalities in the labour market, but instead I argue for a greater recognition of how those who do not have the benefits of an advantaged background can also be insulated by their families. I have written about this in more detail with Ciaran Burke in a recent article for the British Educational Research Journal.

In my PhD, I explored ‘uncertain’ graduate transitions into the labour market and individuals who found it difficult to find a firm footing as they started their working lives. Many of my participants were first generation university students and did not come from advantaged social backgrounds. Findings evoked the enabling but also limiting role of family. I used a social theory (not used in mainstream careers research) to illuminate issues of identity. In our article, Stories of Family in Working Class Graduates Early Careers (Christie & Burke, 2021) we borrow the word ‘salience’ from the work of Dorothy Holland and her co-authors (1998) and ‘distinction’ from Pierre Bourdieu (1984), to capture the different depictions of family. Both articulations of ‘salience’ and a search for ‘distinction’ emerged in how graduates’ stories responded to family.

Most immediate responses from research participants would be to dismiss the role that family had in influencing career decisions and that their career was a sole authored journey. However, follow up questions often revealed the slippery nature of these claims of independence. Examples of ‘salience’ included the important role of siblings but also of mothers’ late return to education. There were also some expressions of solidarity with a working class background and a rejection of an aspirations-deficit discourse. In contrast, some graduates did more clearly seek to be distinct from their families, which fits with a classic Bourdieusian analysis in which an uncomfortable separation occurs as working class people are ‘a fish out of water’ in more professional contexts and appear to need to dissociate from family, in order to move into a different world that seems remote from their background.

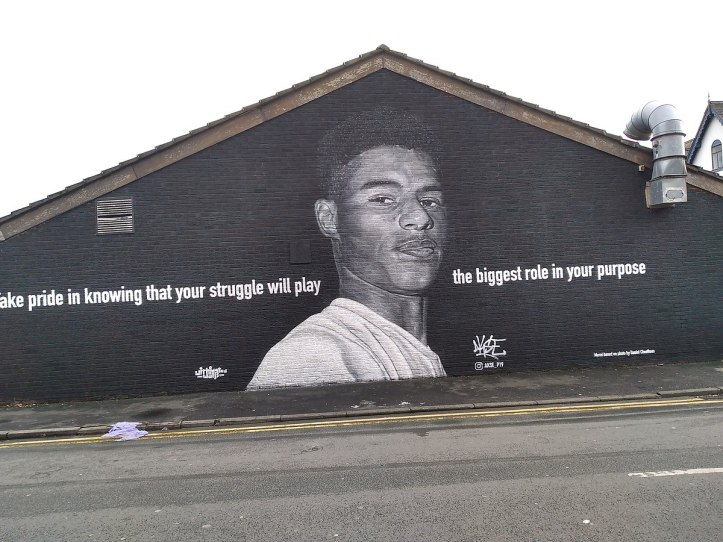

I would argue that there are implications for careers educators and practitioners to foster student reflexivity about family sensitively, and to be aware of how family backgrounds may influence graduate career paths and students’ awareness of wider inequalities. I do not propose that careers practitioners start asking intrusive questions about individual backgrounds. However, sensitivity to different backgrounds is important to appreciate the varied resources that individuals bring to their hoped for career. It is valuable to encourage individuals to consider what they do have in terms of networks and social support rather than focusing just on what they may lack. We need to change the discourse of networking, which is narrowly focussed on useful social connections and social capital, and creatively find ways to appreciate diverse resources. In the public eye, Marcus Rashford is a great example of someone whose successful campaigning for Free School Meals for schoolchildren has been grounded in his own socio-economic background. He received Free School Meals as a child and his family used food banks when he was growing up. His story resonates of the classic rags to riches tale, but in his case, he draws positively on his background rather than implying that his success as a Manchester United footballer was in spite of where he comes from.

The role of family has come into sharper focus due to Covid-19. On a daily basis, we hear stories of families thrown into greater dependence, whether it be for home-schooling or care of the vulnerable. For some family relationships can be toxic, while for others they provide invaluable anchorage. Careers practitioners can be alert to such differences and be sensitive to the diversity of what family can represent for individuals.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction : a social critique of the judgement of taste. London: London : Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Christie, F., & Burke, C. (2021). Stories of family in working-class graduates’ early careers. British Educational Research Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3689

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

I’ve become increasingly uncomfortable with the way that careers practice can often construct families and relationships as a problem. Most of us live our lives with a number of close relationships (partners, parents, children and friends). I think that we should recognise that these relationships are a part of our career (our life journey) rather than either a challenge or a help to a version of career that is defined as our paid working lives. The implications of this are fairly huge of course both for careers practice and for wider policy. If family and relationships are made more central and economic relationships less central we are starting to move towards a new and different kind of society.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I could not agree more Tristram. I am also sensitive to how practitioners’ own experience of family and relationships will affect their view of this. We should be aware of our own biases. Attitudes to family also change over time. I confess myself to being slightly embarrassed by my Irish parents when I was 21 and how I perceived their old-fashioned ideas (compared to peers who seem to have much more sophisticated parents). Many years on, I am enormously proud of what they achieved having left Ireland in the 50s and very conscious of what they gave to me and how my story connects to theirs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

More depth from my tweet Fiona:

I love this topic. I completely agree. We cannot make any assumptions based on family background or any other characteristic. I also find it difficult to interpret what people ‘lack’ from their habitus / social capital or family background. Without fully understanding their background, how can you know? It is impossible to get a full understanding with an infinite amount of time, never mind a short career intervention. With all the career models in the world, who is anyone to say, you need this, or you lack that, especially from a social, family structure and support context. It’s easier to identify certain qualifications, skills and experience for a particular job. I think being sensitive to family backgrounds and focusing on helping students to identify their strengths and resources is the best way to go. Especially in guidance situations.

But from a wider strategic point of view we should also facilitate a journey or experiences where students can realise what strengths others have from their family which they may not have and identify things that they did not even know existed. We do facilitate this in workshops and through discussions, peer to peer support programmes like mentoring etc.

This article mentions feeling a ‘fish out of water’ in more professional contexts, I would love to see the research on that, focusing on why they felt out of water? What support or experiences would they have liked to have which could have helped them feel more comfortable?

A response could be at a professional social event, the dining etiquette may have been more formal than some working- and middle-class people are used to. The style of dinner, the food, the cutlery etc could have been alien to them. This could have made them feel like a ‘fish out of water’. They had to focus on the etiquette, not making a fool of themselves. Which meant their confidence was diminished, attention to the conversation and networking opportunities were not as strong as they could have been. The result of that feedback could be that in these formal situations some working-class people might miss out on connecting with contacts who could be a key influencer in their career prospects. This scenario can be replicated in more situations than just formal dinners.

That is why I think careers development needs to be a consideration within all aspects of the student journey. We have career appointments, we deliver career development workshops outside of the curriculum and embed career learning into the curriculum, there is some brilliant work on extracted employability now too. But to address the cultural barriers to career awareness and progression we need to be more subtle and work with all other departments too. We could work with Alumni teams to receive social and cultural feedback. Then if the dinner scenario is common, we could encourage student life, union teams to run more formal social events following formal etiquette. There could be other feedback and barriers which other departments could help overcome too. This is just an easy example.

I am a big fan of planned happenstance too, so I like the idea of working with all departments to facilitate opportunities for students to develop, opportunities which increase the probability of meeting someone, or achieving something which was unplanned and makes a positive impact on their career awareness and prospects.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Chris, thanks for your reply. Really valuable points. I am glad post resonates with your experience. There is a careful path to tread which avoids a deficit focus on what people lack, while also recognising inequality.

I also think we can move more to considering young people as whole people with complex lives including work, study, family relationships which require trade-offs.

Careers practitioners can also influence employers to consider how qualities they may seek in candidates are associated with more advantaged students, eg., is a polished performance at a formal occasion really a requirement of the job.

I agree with you that careers services should play an important role in fostering new connections and relationships which may be particularly beneficial to working class students.

LikeLike