My reflections in this post are based on my career guidance practice in English universities as well as my research into graduates’ early careers. Though based on England, I hope the post will be of interest more widely. The Covid-19 context for the Class of 2020 led me to want to write about what I learned about graduate transitions in research I conducted between 2015-17.

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated many fears for the class of 2020 graduates; and as practitioners, we will need to help students and graduates make sense of the current situation. I suspect that the very stark economic and social shock will contribute to an unusually high level of awareness amongst graduates of structural issues that influence career possibilities. Historically, much career development and employability practice in universities prioritises individual agency rather than highlighting inequalities and labour market conditions. The current challenging labour market context means such an emphasis on the individual is not enough, and we will need to find ways to talk about structural issues without overwhelming students and graduates about the uncertainty that surrounds us all.

Current challenges risk amplifying inequalities in the job market, as individuals compete for quality jobs. Now (perhaps more than ever) must be the time to encourage students and graduates to think critically about the impact of structural and contextual factors upon hoped-for careers. Career guidance can help in this process.

In my research, I created a typology to categorise how graduates reflect upon careers. I introduce the typology in this post as an accessible tool to help surface discussions about structure and agency with scope to foster critical consciousness. Such consciousness is argued for in work about social justice in career guidance.

What led me to do research about graduates?

In my practice as a careers consultant in English universities, the bulk of my work was with students. Interactions with graduates were much fewer. I met those with successful stories to tell who returned to talk to current students as part of modules. I also saw graduates as part of one off career development programmes, or the occasional one would appear in my appointment diary. The small number of graduates who actively sought advice tended to be facing challenges and came to the careers service for help. Numerous individuals and their hopes and fears still linger in my memory.

My interactions with graduates made me realise I only had a partial understanding of their early careers although ironically I spent most of my working days advising students about graduate careers. As a practitioner, I spent a lot of time encouraging and motivating people. I constantly juggled encouraging a positive attitude while knowing how hard it could be for graduates to get onto the right path.

So when the chance came up to do research as part of my PhD about graduates’ early careers and transitions, I jumped at the chance. I wanted to plug the gap in my partial knowledge.

I was most interested in finding out more about those for whom transition have not been smooth. I was curious to test the truth of claims I’d heard from Charlie Ball, the graduate labour market expert that graduate unemployment tended to be a short-lived experience. I also wanted to explore whether Elias and Purcell’s argument that it took about three years for many graduates to settle into a career still had value, despite many university marketing statements promising more immediate returns to a degree.

What I found out from my research into graduates?

The first stage of my research was to do a survey with graduates fifteen months after graduation. My target group were 2014 graduates of Arts, Creative Arts and Humanities as well as Business and Law (effectively two school of study at my host university). Responses to the survey (n148) showed that two-thirds had changed their career ideas and plans since graduating. There was evidence of steady improvement in circumstances too, e.g., unemployment did seem to be a temporary experience for most. Many had experienced some under-employment but again this was often short-term. Across the data, a picture emerged of early turbulence with both good and bad experiences being part of normal patterns. My findings supported that there was a lot of movement and change in early careers and that this was generally OK for most. Most graduates were still not in a settled position at fifteen months.

I wanted to delve further into how graduates made meaning of this early turbulence through research interviews (n20). Throughout interviews, it was striking to observe a commonality across graduates. They tended to have a deep personal engagement with regard to what they wanted in a working life. Individuals often expressed views which suggested they measured their own worth as people in whether they were successful or not in a hoped for career (the terms of that success varied across graduates depending upon their values). Arguably, this personal investment does reflect dominant individualistic discourses, which lead people to downplay contextual issues that may impact on their likelihood of success, however they define it. Graduates appeared to engage less in reflecting upon structural inequalities or labour market conditions when considering their circumstances. However, contextual factors mentioned included everything from frustration with what they’d gained from their degree, to a lack of social networks, to reflections upon unfair employer practices and inequity in competition for jobs in certain sectors.

A typology of ‘voices’ about careers

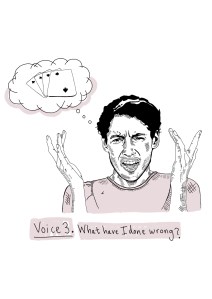

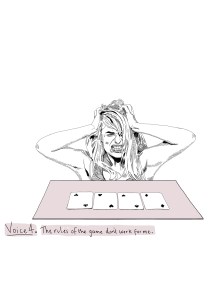

I observed how graduates drew upon different and often competing cultural ‘voices’ in order to evaluate and make meaning of their situation. I used social theory and the wider careers literature to inform my analysis, which helped me identify what those ‘voices’ might be. In brief, I identified four ‘voices’ and crafted associated statements to capture how individuals evaluated their career positioning. I named these;

‘idealistic’ – if I am true to myself, I can control my destiny,

‘self-critical’ – what have I done wrong,

‘tactical’ – I need to work out how to win at this game,

‘context-critical’ – the rules of the game don’t work for me.

My son also created images for them.

Many of you will notice that I have adapted ideas from Bourdieusian social theory (the ‘feel for the game’) in doing this. I concluded that those who moved between these different ‘voices’ rather than getting stuck in one seemed to have a greater ability to tell their story reflexively and demonstrated glimmers of what Blustein and his co-authors have called critical consciousness.

Implications for career guidance and social justice

A social justice approach to career guidance supports the development of critical consciousness and I have used the ‘voices’ typology with students in my teaching to highlight different social norms and assumptions about careers. The typology is easy to explain and grasp and I’ve used it to trigger discussions about structure and agency. I have observed a tangible sense of recognition amongst some students when I describe the ‘voices’; for example, when I’ve explained the ‘self-critical voice’ and how some individuals may berate themselves incorrectly about a lack of success. In my practice and research I’ve noticed that people can take rejection in job-hunting very personally, assuming that a failed job interview is somehow a verdict on them as a person. This can inhibit confidence in continuing to apply for jobs. Career guidance can be part of the safety net to help people to keep on going and adapt what they do in such circumstances; it can help people recognise what is and isn’t in their control. My experience tells me that the ‘context-critical voice’ is one that individuals struggle to manage the most as it can be overwhelming to consider the range of factors that act as barriers, although it is crucial to recognise these.

Public policy and the value of a degree

Finally, based on my research and practice, I would argue that current public policy in England and the UK which evaluates the value of a degree based on the Graduate Outcomes census at fifteen months (formerly six months) as well as on tax data through LEO (at one, three and five years) ignores the complexity of how graduate careers develop. This complexity is going to be even greater for the class of 2020. I support calls for a different way to measure the value of a degree, which can capture the different success criteria that individuals may have (eg., HEPI, UUK). Outcomes are often unequal and influenced by range of social and demographic factors such as class, gender and ethnicity. Solutions to such inequalities will require collective action from government, employers, universities and graduates themselves. At this time, our priority for public policy as a society should be finding creative ways to support all graduates especially those from less advantaged backgrounds to navigate uncertainty and turbulence. Due to the pandemic, there will be an enormous caveat surrounding Graduate Outcomes data for both 2019 and 2020 graduates, casting doubt on that data’s claim to be a measure of universities’ abilities to produce employable graduates.

Did you find that individual graduates tended to exhibit one of these voices? e.g. were there ‘self-critical’ grads and ‘context critical’ grads. Or were multiple voices found in a single graduate?

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Tristram. It varied – but many would move between voices. Things aren’t static and I don’t intend to box people off as people change over time. But some might get stuck in just one. Those who move between ALL ‘voices’ rather than getting stuck in one or two seemed to have a greater ability to tell their story reflexively and demonstrated glimmers of critical consciousness. The context-critical voice is a tricky one as it might include awareness of wider social inequalities which is good but may also reflect being a disappointed consumer of higher education which may lead people to blame the wrong entity for a lack of career success (after all universities have limited power over the job market). I think as practitioners, pointing out these different voices all of which are a feature of contemporary attitudes to work is a way to get students to think critically about taken-for-granted assumptions, and wider issues of structure and agency. I think my findings also connect to discussions of ‘locus of control’.

LikeLike

Fiona – thanks for this great summary of all your hard work. I can certainly recognise the 4 voices in my clients.

LikeLike

Really glad to hear that. Thanks for letting me know.

LikeLike

Thanks Fiona, a really interesting summary. The four voices typology seems like a really great tool for fostering critical consciousness and I can see how it could lead to some fruitful discussions and reflections. I’ll definitely be sharing this with my team.

LikeLike

Thank you. I hope it provides a useful and straightforward way to raise discussions with colleagues and students about making sense of career positioning.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Fiona, this work is interesting. Did you see any connection between the voices and behaviour in terms of some precluding action? Also were there any Connections spotted with mental health challenges?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good questions. My main focus was on understanding meaning-making rather than an explicit consideration of connections to action or mental health. However, I observed that the self-critical and context-critical could act to inhibit action and may make people feel more negative. But my view is that an ability to draw on all voices (possibly not at the same time of course) can lead to greater critical consciousness and more productive action. This is a challenge for careers advisers to help people view the world positively without ignoring contextual challenges and personal barriers. A delicate balancing act.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Turbulence in early graduate careers: the implications for career guidance. Fiona Christie’s piece based on her research with graduates highlighted the difference career voices that students adopt when thinking about their futures. […]

LikeLike