In this post Tony Watts discusses his visit to South Africa during the apartheid era.

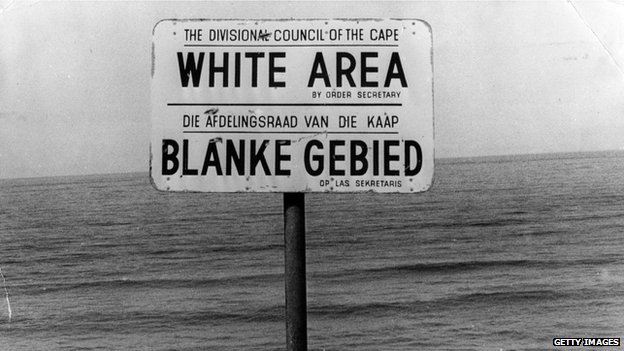

In early 1978 I received an invitation to give some lectures at a conference on Guidance in the Classroom – in Preparation for the Eighties to be held at the University of Cape Town in October of that year. South Africa had become a prime focal point for the world’s guilt and confusion about racial discrimination and about the denial of basic human rights to particular ethnic groups. At the time there was an academic boycott of the country, designed as part of international pressure to force an end to its system of apartheid. I had strong views about apartheid, but I had never been there, and I wanted to see it for myself. Eventually, after much wrestling with my conscience, I agreed to go, under two conditions: that the conference should be multi-racial; and that before giving my lectures, I should have an opportunity to visit career guidance services in different parts of South Africa and seek to understand them. The trip proved to be, for me, a transformational experience.

The visit

The visit was organised by the British Council. I had several friends who were from South Africa or had spent time there, and with their help I carefully drew up a list of who I wanted to see. All my requests were agreed.

I visited several career guidance services in the so-called White areas. But I also wanted to see the services for the Black community, who formed 72% of the population.

Most Black people were concentrated in the ‘bantustans’ (‘homelands’), which comprised 13% of the country’s territory: reservations of varying size, mostly small and scattered, based in areas poor in mineral resources. I visited one of these bantustans: the Ciskei.

However, the economy in the bantustans was limited largely to subsistence farming in conditions of considerable poverty and malnutrition. To find work, many men had to go to the White areas, where all the wealth and economic resources were concentrated. This was the key to the logic of apartheid policy: White industry was heavily dependent on the supply of cheap Black labour. So Black men were encouraged to move to work there, but under strict and severe restrictions. Some qualified for permanent residence in the urban townships. I went to one of these townships: Soweto.

The Government was though concerned to limit the numbers given such permanent passes. So there was an additional, highly flexible pool of Black workers who were permitted to work in White areas for 12 months, after which they had to return to their bantustans for at least a month before they could re-apply for work. They were not permitted to bring their wives and children into the areas where they were working. Some, however, did so, illegally, in shanty towns which periodically were bulldozed by the police. I visited one of these shanty towns: Crossroads, in Cape Town.

I thus went to all three of the main types of location in which Black people lived. Many of the White people I spoke to had never visited any of these. Of those who had done so, few had visited more than one.

In the course of my visits, I had many intense conversations. A lot of White people were concerned to persuade me that their country was a liberal democracy (which in some respects it was) in which separate development meant that the distinctive needs of Black people could be addressed and respected. But the Black people I met, and what I saw, told a very different story, as did the more perceptive White people. I also spoke to some in the Indian and Coloured (mixed-race) communities, who tended to have an intermediate status between the two larger groups: they, too, provided a distinctive critical perspective.

Some key experiences

My findings from my visits were described in detail in an article I subsequently wrote on Career Guidance under Apartheid, published in the International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling in 1980. Each ethnic group had its own education system. The most important conclusion was that the career guidance in White schools was reasonably well-developed; but that in Black schools it was a sham, designed to maintain a pretence of choice when virtually none existed. Few Black schools had counsellors, and much of their limited time was spent on administering tests, the results of which were used more for statistical and research purposes than for guidance purposes.

In these notes, however, I want to record some key experiences which were too impressionistic to be included in an academic article.

The first was my visit to a school in Soweto. This was two years after the Soweto riots, in which many thousands of schoolchildren had protested against the introduction into the ‘Bantu’ education system as the medium of instruction of Afrikaans, which they perceived as the language of oppression. Several hundred young people had been killed by the police in the riots. The atmosphere was still febrile. I was accompanied in my visit by the Director of Education, an Afrikaaner. When we entered the school and met the Black school principal, the Director of Education went up to him and tugged his lapel. It was a blatant and unmistakeable assertion of power and threat, warning him to tow the official line in what he said to me. To do this so overtly and unapologetically in the principal’s own school was utterly shocking. It only lasted a few seconds, but I have never forgotten it.

The second was my visit to Crossroads. I saw no other White person during this visit. I was accompanied by a young man who was Coloured and knew many people there, so I felt totally safe. The families were living in conditions of abject poverty, under pieces of corrugated iron, in constant fear of the next visit from the police bulldozers. I recall one of the families inviting us in for a cup of tea. I was deeply moved by their stoicism and their hospitality.

The third was a conversation I had with Fanyana Mazibuko. He was working at a higher education non-governmental organisation (NGO), and I had forgotten why he had been recommended to me. But I learned so much from the hour or so I spent with him. He had been a friend of Steve Biko, a prominent anti-apartheid activist who had been killed in police custody in September 1977. He talked about Biko and what he stood for, and many other things. He told me that he was a pacifist, and could not advocate violence. But he also told me that the repressiveness of the South African state was now such that he could no longer argue against violence.

I also remember going to a performance of Athol Fugard’s visceral play Sizwe Banzi Is Dead at the famous Market Theatre in Johannesburg. The play dramatises the racist brutality of the apartheid regime in general and the pass laws in particular. I saw it again a few years later in New York, when it received a noisy and passionate reception, with the audience responding to its resonances for the USA. But in Johannesburg, in the midst of the society which the play was directly depicting, its reception was muted and repressed. Some Black people were present, but in the interval they huddled in separate groups. It was as though the drama was too close, too relevant, and too unsafe to respond to in an overt way.

The career guidance service which interested me most was a small non-profit organisation: the Careers Research and Information Centre (CRIC) in Cape Town. It was attached to a community agency, the Foundation for Social Development, financed largely through philanthropic funds from industry. It had been set up following a needs analysis by its Director, Shirley Walters, which focused mainly on the needs of Coloured people, on the grounds that employment opportunities were rapidly opening up to them and that they were the largest population group in the greater Cape Town area. But CRIC had been established explicitly as a ‘non-racial organisation’ to enable it to interact with all ethnic groups, including White teachers and pupils, so providing one of the few places where teachers and students across racial classifications could meet; and also, where possible, to facilitate the opening up of opportunities to the Black community. Staffed by five enthusiastic young workers, it was operating at the interface between service delivery and political engagement, with the pressures and tensions that this involved. It was attracting growing interest, and seemed to me to provide a promising model for parallel initiatives in other parts of the country, which might provide a beacon of hope.

The conference

So we came to the conference at UCT. The proceedings were published, so I have a record of the discussions, and my contributions to them.

I had been asked to give four lectures. In my opening lecture, I talked generally about concepts of careers education, but I also included some comments, based on what I had learned during my visits, about the South African career guidance system in general and provision for the Black community in particular. I emphasised that I was very conscious that my comments were those of an outsider based on brief experience, but that I hoped they might be helpful.

On the paucity of guidance provision, even basic career information, I noted that this was hardly surprising: most Black people were deprived of opportunities; if this was to be so, they clearly needed also to be deprived of access to information on those opportunities. I had been told by some that this was now changing, but I questioned how far this was to be allowed to go: in particular, would Blacks be allowed to compete in any meaningful sense with Whites for jobs; if not, then the ambivalence about access to information and guidance was likely to continue.

I also noted that from my conversations with students in Soweto and elsewhere, it was clear that for the few higher-achieving Black youngsters who had choices, their most important career decision was not between becoming a lawyer or a teacher, for example, but between three rather broader options: first, to follow the conventional route to individual advancement, which would be seen by some in their community to be a form of betrayal, of ‘joining the Whites’; second, to do this but in a way which made it visibly clear that their goal was to make their developing skills available to their own people – which in a place like Soweto would be likely to be interpreted by the authorities as political activism and therefore repressed; or third, to reject the traditional education and career system and look for alternative forms of education which would help in securing social and political change.

It was clear that most people at the conference had never thought of career guidance in this way. I was listened to reasonably respectfully, but the issues I had raised were not taken up in any of the subsequent contributions. By the time I came to my third lecture, I felt that I had to make one more effort to raise them. I agonised about how to do it. This was what I said, as recorded in the transcript:

I am due to talk this afternoon about designing and co-ordinating a careers education programme. First, however, there are one or two important things that I want to say. I don’t know whether I should say them, you may not like my saying them, but I want to say them and am going to say them.

I am feeling confused about this conference. I am not quite sure whether this is because I feel uncomfortable or because I feel too comfortable…. From listening to the discussions here, one would never know that 83% of the population in this country are Black, Indian or Coloured. We seem to talk all the time as though that 84% do not exist. So far this has been a White conference, about White kids in White suburban schools. Yet it is supposed to be a multi-racial conference (indeed, if it had not been multi-racial I would not have accepted the invitation to come). There are people here from other ethnic groups, but we have not heard very much from them. Perhaps this is because we have not given them much chance to talk about their problems… I do not know why this is. I do not know whether it is because we are trying to suppress the fact that the Blacks exist, or because we are not interested, or because we feel a sense of powerlessness to do anything. But the fact is that for almost all the time I have no sense that we are talking about anything other than White kids.

The time when this hit me most forcibly was late yesterday afternoon when we were talking about family guidance. There were some value assumptions in Mr Olivier’s talk with which I personally disagreed. They seemed in fact to be at variance with a lot of the things which have been said by people at this conference. Yet for some reason we did not explore them… There appears to be an inability to tolerate conflict… Also, … what is the role of family guidance for Black kids, many of whom are going to become migrant workers and therefore part of a system which is designed systematically to break up the family unit? Nobody mentioned this. It has been mentioned outside this room – several people have come up to me and talked about this and similar issues. Yet none of it is coming into this room.

This is something to do with the boundaries we are placing on our discussions. This is a key issue not only for the process of this conference, but also for guidance in the classroom, which is the topic of our discussion. The conference is sub-titled ‘In Preparation for the Eighties’ and almost everybody I have spoken to has told me about their fears and hopes – but mainly fears – about what is going to happen in South Africa in the next few years. If you are going to help yourselves and your kids to prepare for the Eighties, you have got to recognise that the Blacks are still going to be here and that if the Whites are to survive, they have got to find some way of living with them. This is the biggest challenge for guidance. So what I would like to do now is to provide a little space for anyone who would like to say something about these issues. In particular, it would be good to hear from people who teach in non-White schools about the problems they face.

For about 15-20 minutes, several non-White people spoke, sometimes hesitantly, often movingly, about their situations and the issues they had to confront. Then I went back to the lecture I had prepared. I doubt whether most people listened to a word I said. There was a strange atmosphere in the room, of confusion and repressed anger. At the tea interval, very few people came up to me. A fair number, I soon learned, felt that as a visitor I had overstepped the mark. They were also disturbed by some of the issues that had been raised.

I later commented on this in my IJAC article:

This kind of blinkered vision, suppressed emotion and dualistic thinking are the product of apartheid. White people survive psychologically in South Africa because, for much of the time, they are able to hide themselves from the realities that surround them. Yet, however effective this may be in the short term as a coping device, it ultimately only exacerbates the problems. For it deprives people of the experience which would enable them to come to grips with the realities, and it allows their fears to be fuelled by fantasy. That this seems to be as true of the counsellors as of the rest of the White population must grievously impede their ability to help young people deal with the huge personal problems that face them – including not only guilt and fear, but also the hard and concrete decision of whether to stay in South Africa (with, for boys, the military obligation this implies) or to leave. These problems are immense enough now: they will almost certainly become greater still as South Africa moves into the 1980s.’

But, I added:

South Africa is not the only country where the structure of careers guidance reflects political structures. Nor is it the only country where opportunity structures are severely restricted for particular social groups. It is easy for British people, for example, to off-load their own guilt about inequalities in Britain on to South Africa. This is hypocritical for two reasons: first, the South African economy is substantially maintained by its links with Britain; and second, Britain too is subject to deep racial and social divisions, even if they do not take the distinctively rigid form that they take in South Africa. The fact is that in Britain, as in South Africa, careers guidance is a deeply political matter, because it is essentially concerned with access to power, status, and wealth, as well as with opportunities for self-fulfilment. If guidance staff deny this, they are almost certainly aligning themselves with the status quo.’

Finale

After the conference there was a party, at which many of the people I had met were present. After all the intense experiences of the preceding three weeks, I felt able to relax. I was in a group where we started to talk about the greatest rugby try we had seen. The relief of talking with enthusiasm about something so wonderfully trivial was extraordinary.

The following day, I flew home. As I was looking out of the window, I put on my headphones to listen to some Beethoven, and the title of the movie Cry the Beloved Country came into my mind. I started to weep, uncontrollably, in a way in which I had not wept for many years. The stewardess came to serve some lunch. As a male, I felt ashamed of crying, and tried to hide it, but I could not stop. I thought of all the amazing people I had met, in the beautiful country over which we were flying, and I feared for them.

Epilogue

Then, miraculously, a decade or so later, serious change began. With growing domestic and international pressure, and fears of a racial civil war, Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990. He and F.W. de Klerk led negotiations to end apartheid, resulting in the 1994 multiracial general election in which Mandela led the African National Congress (ANC) to victory and became President.

Meanwhile, a substantial number of non-profit community-based career centres based on the CRIC model had been established across the country, and had formed themselves into a South African Vocational Guidance and Educational Association (SAVGEA). It was a time of great excitement and promise, alongside recognition of the scale of the challenges faced by the new government in creating a more just and equitable society. Later in 1994 I was invited by SAVGEA to visit South Africa again, to help them develop a national strategy for career guidance which could harness the experience and creativity of these organisations in transforming the more formally-based services inherited from the apartheid regime.

Two experiences from this second visit were particularly memorable. Soon after my arrival, Tahir Salie – now Director of CRIC – invited me to join him for lunch in the Parliament buildings in Pretoria. He knew many of the new ANC MPs and we spoke to several of them. A demonstration was taking place just outside the Parliament gates. They told me how strange it was to be on the inside, when only a few months previously it was they who had been the demonstrators. Later I attended a session in Parliament, and there they all were: Mandela, de Klerk, and Winnie Mandela in her colourful tribal robes.

The following day, Tahir drove me to visit one of the community-based career centres. We got lost. Driving past a police station, Tahir said that he would stop and go in, to get directions. He expressed some anxiety about doing so, but decided that he would. A few minutes later he emerged, simmering with repressed rage. They had humiliated him, because of the colour of his skin. Governments can change quickly, but public bureaucracies do not.

By the time of my third visit, in 2009, most of the non-profit community-based organisations had folded, but their influence was still evident. Shirley Walters was by now Professor of Adult and Continuing Education at the University of the Western Cape (an historically Black university) and Chair of the South African Qualifications Authority. I was invited to give the annual SAQA Chairperson’s Lecture (see the text of the lecture), to suggest ways in which a strategy for career development might be developed in South Africa, drawing from international exemplars but also grounded in the indigenous realities of the country (see our article Navigating the National Qualifications Framework (NQF): The role of career guidance).

One of the exciting possibilities being considered, following a report by Trish Flederman (one of the CRIC workers in my first visit), was to establish a career helpline which would reach out into rural as well as urban communities, recognising that most young people, even in impoverished communities, had a mobile phone. I suggested ways in which this project might learn from career helplines in other parts of the world, including the UK (see our article Career helplines: A resource for career development).

I was again invited to give the SAQA Chairperson’s Lecture in my fourth and final visit, in 2014 (see the slides from the lecture). By then the helpline had been established, as part of a range of multi-channel services, and the basis of a national strategy was in place in the form of a Framework for Co-operation between SAQA and the Department of Higher Education and Training. I was asked to comment on how the strategy might be developed and improved, which I did. But I noted that it already represented one of the most impressive strategic frameworks I had seen in this field from any country, including high-income OECD countries, and had the potential to become a beacon for many other countries in the world.

South Africa is a pivotally important country, spanning as it does different cultural traditions and stages of economic development, and with its recent history of overcoming apartheid and building a democracy. It still has enormous problems, not least in overcoming the massive inequalities which are the legacy of apartheid. But it has made inspiring progress. Career guidance has a critical role to play in bringing together learning and work, and helping individuals of all colours to construct their pathways between the two. It has been a great privilege to observe the changes that have taken place, and to have played a small role in supporting them. I am glad I accepted that invitation in 1978.

I think that this post from Tony on his experiences in South Africa is so important. It reminds us that things change and develop and that career guidance has a role to play both in challenging oppression and rebuilding new kinds of society.

LikeLike